My Child, We Never Stopped Searching for You

- Jin Yang

- Sep 26, 2025

- 6 min read

Updated: Sep 26, 2025

Narrator: Yang KX

Chinese Draft: Jin Yang

English Translation: Fengxue Zhang, Peter Zhe

Editor: Clyde Xi

Introduction

China’s one-child policy, enforced for more than three decades, left behind countless untold tragedies. Much has been written about the children who were separated from their families, yet one group of victims is too often overlooked—the birth mothers.

Behind every abandoned or relinquished child was a mother forced into impossible choices: to hide, to flee, to part with her own flesh and blood under crushing pressure from the state and from cultural expectations. Their voices were silenced, their grief endured in secret.

By sharing this mother’s account, we honor her courage and acknowledge the pain and suffering endured by so many women during that dark era. May the world never forget this massive, man-made tragedy—and may remembering help ensure it is never repeated.

Early Life and First Daughter

My name is Yang KX, born in 1968, in a rural village in Wuhu City, Anhui Province. On May 5, 1987, I married my husband, Zhu DR. A year later, we welcomed our first child, a daughter.

At that time, each household was allocated farmland. Our family of three received just over four mu (about two-thirds of an acre). After paying the state grain tax, the remaining harvest was ours to keep. We poured all our energy into growing grain and vegetables. Though life was difficult, at least we had enough to eat.

In 1991, hoping to earn more income, my husband and I left the village to work in Wuxi City. My father-in-law tended the farm in our absence.

But the government’s family planning policy weighed heavily on us. Only one child was allowed. A second pregnancy could bring crushing fines, forced sterilization, and lifelong consequences.

Hiding from the One-Child Policy

In our village, many elders still clung to the belief that only sons carried on the family line. We hoped for a boy, too, though we cherished our daughter dearly.

When I became pregnant a second time, I dared not return home. I moved from one relative’s house to another, always hiding from the family planning inspectors. Ultrasounds and gender testing were forbidden, so we could only wait in secrecy.

Eventually, in a small, distant clinic, I gave birth. It was another girl. We loved her instantly, but we could not let the village know. Terrified of discovery, we entrusted her to my husband’s older sister. She raised our daughter until she was five, while we secretly provided support. No one in the village ever knew.

We returned to migrant work. In 1995, I became pregnant again. The decision nearly tore us apart. If it was a girl, we faced fines and sterilization. If it was a boy, we were willing to endure the punishment for the sake of the grandparents’ hopes. Finally, we decided to take the risk.

The Pain of Letting Go

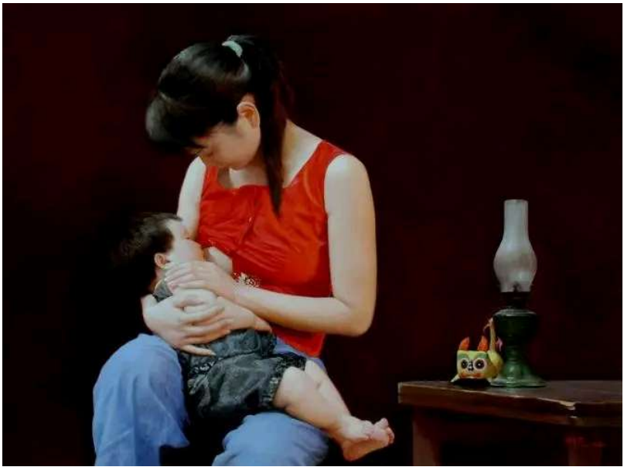

On July 16, 1996, I secretly gave birth to our third child. She was another girl—healthy, beautiful, and perfect. For 40 days, I nursed her. Those days were filled with tender joy, but also dread. We knew we could not escape the policy forever.

We searched for a childless family who could raise her. Eventually, we heard of an elderly woman in a nearby village who had relatives in Chaohu City, a family said to want a child. With hearts breaking, we entrusted our baby to her—along with her birth date and time.

The village never knew. We returned to work as if nothing had happened. We could only guess that our daughter was somewhere in Chaohu City. In Chinese custom, once a child is given away, biological parents are expected never to interfere. Many times, I longed to ask the old woman for details, or just to glimpse my daughter from afar. But her family suffered a terrible tragedy—her own son was executed for murder. I dared not disturb her pain.

Searching in Desperation

Years passed. By 2004, our daughter would have been almost ten. We longed to celebrate her birthday, to see her, to bring her gifts. That year, we finally approached the old woman. At first, she refused to give us any address, insisting the adoptive family did not want to be disturbed. We persisted. At last, she reluctantly gave us an address in Chaohu City, thinking we would not go.

But we did. After a long journey, we arrived at the house—only to discover that the family had never adopted a child. Terrified that our daughter had been sold, I rushed back and confronted the old woman. I refused to leave until she told me the truth. Finally, under pressure, she admitted she had sent our baby to the Gaoyou Welfare Institute in Jiangsu Province.

My world collapsed. How could she abandon my child to an orphanage? She swore she was telling the truth, claiming the institute director was her relative and that families who delivered children there could gain welfare benefits.

That same day, we took an expensive taxi to Gaoyou. My heart raced with terror. Was my daughter safe? Had she been mistreated? Regret and self-blame nearly consumed me.

At the orphanage, the staff denied us entry. I broke down, sobbing, until the police came. At last, after I named the director, a retired leader of the institute arrived. He agreed to check the records. Based on the birth date and details, he quickly found her file.

When I saw her photo, I knew instantly. Still, I asked him to confirm, pretending not to recognize her. He assured me it was indeed my daughter. I secretly photographed that picture—it is the only image of her I ever had.

When I asked where she had gone, the director said only that she had been adopted by a well-off family. If she ever came searching, they would give her our contact. From his tone, I feared she had been sent abroad, though I dared not ask.

We left devastated. We returned in 2006, 2008, and 2010, each time leaving new phone numbers, each time returning in despair.

Hope and Reunion

As the years passed, our son grew up. He understood our pain and helped us search. In 2018, he posted our case on the “Baby Come Home” website, and even appealed to Gaoyou TV, newspapers, and friends. He traveled to Gaoyou himself, but no news came.

In 2023, a volunteer from the “Nanchang Project” noticed our story online. They arranged a free DNA test for us. By then, we had searched more than twenty years.

In the summer of 2024, with the help of Chinese and foreign volunteers, our DNA was uploaded to GEDmatch. To our astonishment, it matched with a young woman in the UK. After decades of longing, we had finally found her.

On July 14, 2024, we spoke to her for the first time over video, with volunteers helping us connect. I wept with joy, overwhelmed with gratitude to her adoptive parents who had raised her with such love.

Few birth families in China ever reunite with children adopted abroad. Thanks to volunteers, we were given that chance.

In May 2025, we traveled to the UK. For ten unforgettable days, we embraced our daughter, met her adoptive parents, saw her friends, and explored the country together. With interpreters from “Bridge of Love,” we shared stories, laughter, and tears. After nearly thirty years, to finally hold my daughter was the happiest moment of my life.

We are forever grateful to the volunteer team who made this reunion possible, and to her adoptive parents for the love and care they gave her.

Appendix – A Volunteer’s Note

Jin Yang, a searching volunteer:

When I saw this case registered on “Baby Come Home” in 2018, and learned the child had been sent to Gaoyou Welfare Institute, I suspected she may have been adopted abroad. The platform made it difficult to reach the family, but I did not give up. Eventually, I reached her sister by phone, and later connected with her brother. He agreed to a free DNA test through the Nanchang Project.

Two months later, through GEDmatch, we found her daughter—who had uploaded her data years before.

In rural China, many families once gave away children—some out of poverty, others to help childless couples. Sons were valued for carrying on the family line, while daughters married into other households. These traditions fed the preference for boys. But with social and economic progress, these customs are changing.

Comments